Three Recent Single-Location Films (and Three Not So Recent Ones)

In the article Why You Should Be Reading Plays, I discuss how plays provide a good example for how to write a contained, single-location script while maintaining strong character dynamics and conflicts.

If you are a screenwriter, you have probably had someone tell you “You have GOT to write a contained thriller!” And really, that advice is true. Now more than ever, producers are looking for good scripts with minimal locations, small casts, and riveting stories.

But what makes single-location scripts work? The best way to construct a single-location script is to devise a premise that possesses a contained scope, or what I like to refer to as a “self-isolating situation”.

A self-isolating situation, in essence, is when something has happened either to a character or in the plot of a screenplay that keeps them tethered to a location. This, in turn, allows the narrative to construct its conflict around that location.

Here are three examples of recent films (and three not so recent films) that are all contained, and what their self-isolation situation is.

THREE RECENT FILMS

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2021)

This is an adaptation of the play of the same name by August Wilson. During a recording session, tensions rise between black blues singer Ma Rainey and her white management. By centering the film around a recording session, the film succeeds in keeping not only its location singular but the conflict streamlined as well.

Many of the films mentioned in this article will use an isolating event to tie their cast of characters down to a singular location, such as a dinner party or a jury summons. Ma Rainey does a fantastic job of this, by centering the film around a recording session.

You can read the script here.

Also worth a shout-out is another adaptation of a play by August Wilson, Fences, which tells the story of a black sanitation worker in the 1950’s and his family. The film is set primarily in the family’s Pittsburgh home, although there are a few scenes outside the house, such as one on a garbage truck. The film benefits from progressing time between scenes, including time skips, so that the action can focus on domestic life.

You can read the script here.

Carnage (2011)

In this adaptation of the Tony Award-winning play by Yasmina Rez, two pairs of parents meet after their children get in a fight. Although they attempt to remain cordial at first, tension quickly rises.

The film expertly keeps to one location by centering it on the parent’s desire to prove who is at fault and then part ways. Yet, neither pair is willing to take responsibility.

By creating the tension around a refusal to leave, the film grounds their location in ever escalating, self-generating conflict.

You can read the screenplay here.

August Osage County (2013)

An adaptation of the Tracy Letts play, it tells the story of a large family who comes together when its patriarch dies. Are you starting to notice a pattern with plays adapted to single-location films? This is why you should be reading plays!

By setting the film around a single home during a funeral, the film generates its conflict between estranged family members who are brought together under uncommon circumstances. While the film does contain a few scenes at the funeral, it primarily focuses on the action at the family home, and their conflicting feelings about one another.

You can read the screenplay here.

Special shout out to Bug, a play turned film also written by Tracy Letts, which documents the mental breakdown of a couple in a motel room, after they suspect that they’re being watched by the U.S. Government.

You can read the original play here.

THREE NOT SO RECENT

Rope (1948)

In this Hitchcock classic, inspired by the Leopold and Loeb case, two friends murder their classmate and try to hide the body—during a dinner party! It’s a fantastic example of how to craft a taut thriller in a single apartment, and nearly a single room.

Trying to imitate the affect of a play, Hitchcock edited the film to appear as if it were shot in one continuous take. Due to the technological constraints at the time, it’s actually comprised of 10-minute takes that Hitchcock obfuscated through clever tricks, such as cutting to a dark corner or somebody’s back.

In this case, the self-isolation situation is that the protagonists are trying to keep a dead body hidden during a dinner party.

You can read the original play here.

Also worth noting is Alfred Hitchcock’s more famous Rear Window, which puts a photographer played by Jimmy Stewart in a cast with a broken leg, with his only pastime being observing his neighbors through his large window—until he suspects he might have witnessed a murder.

You can read the screenplay here.

12 Angry Men (1957)

In this film, a group of 12 jury members deliberate on the conviction of an 18-year-old defendant. As tensions rise when values conflict, their desire to leave the jury room is tempered by their moral obligation to the defendant.

Yet again, the self-isolating incident is a desire for the characters to leave the setting, but they can’t for good reason. In this case, it’s the characters’ values pitted against one another, refusing to leave until they come to a common decision.

You can read the screenplay here.

Exterminating Angel (1962)

A true masterpiece of avant-garde cinema, Exterminating Angel by Luis Bunuel tells the story of a group of dinner-goers who end up both existentially and supernaturally trapped at a dinner party. As they find themselves unable to leave the room, tensions rise and true colors come through.

Here, we begin to see the recurring theme of characters trapped in a single location. However, while in previous films the force keeping the characters trapped inside the house was a personal conflict, here it is external. There is some supernatural force binding the characters to this dinner, and the conflict becomes their inability to leave.

With a subscription to archive.org, you can request a copy of the screenplay, along with two other Bunuel classics here.

BONUS

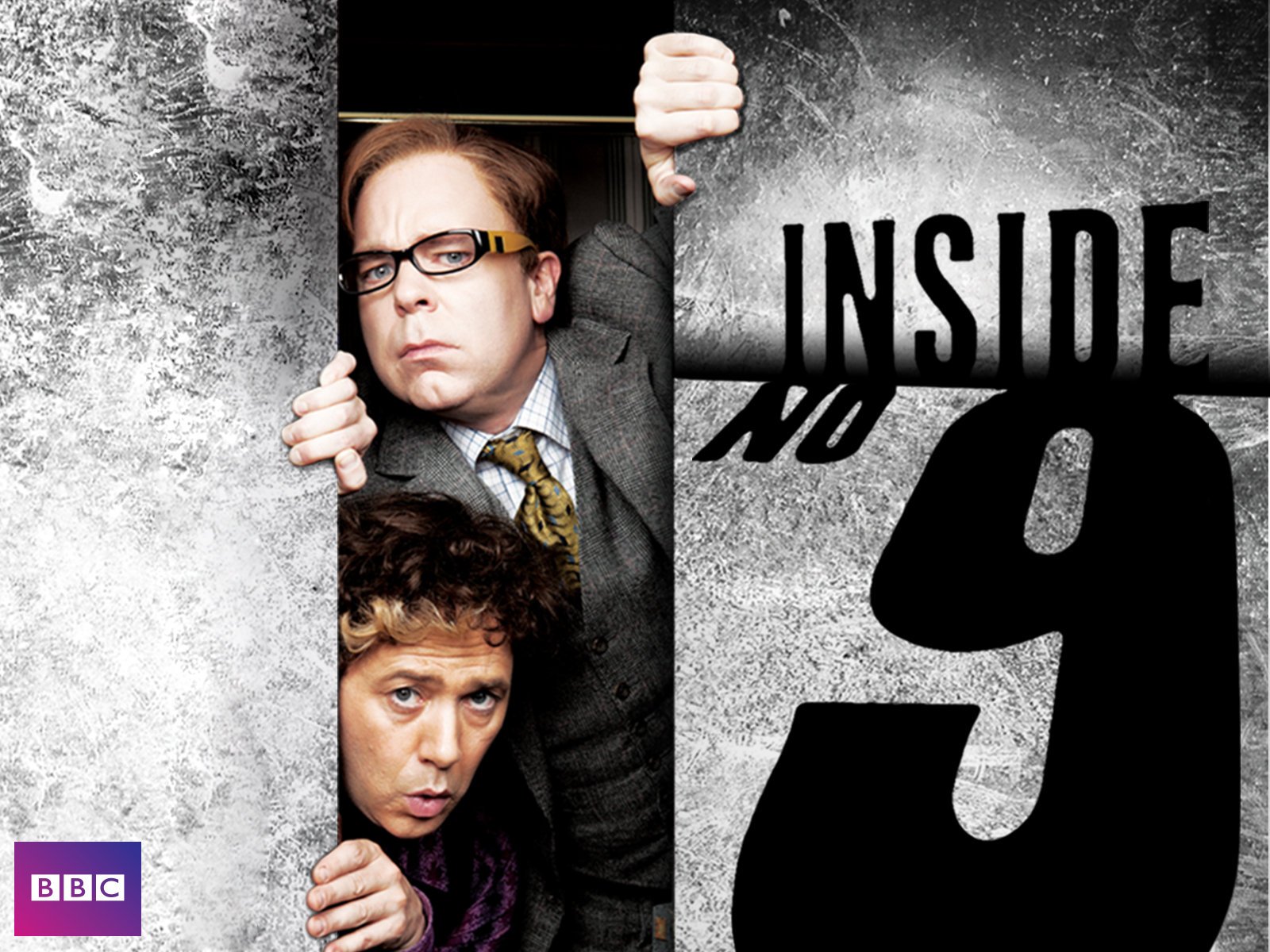

Inside No. 9 (2014-Present)

As an added bonus, check out Inside No. 9. It’s a BBC anthology series by Shearsmith and Pemberton, creators of The League of Gentlemen. While each episode varies from darkly comedic to camp horror, they are all united by this common thread: each episode is contained to one location, and each location begins with the number “9”.

Episodes can be found here.

A particularly noteworthy episode is “The 12 Days of Christine”, which focuses on 12-years of a woman’s life inside her London flat.

You can read that episode here.

Thomas Blakeley is a screenwriter, playwright, and musical theatre bookwriter based out of Los Angeles and New York City. A graduate of The New School, he is passionate about the arts, social justice, and all things nerdy. He can usually be found scouring the horror section of a local bookstore.

Thomas Blakeley is a screenwriter, playwright, and musical theatre bookwriter based out of Los Angeles and New York City. A graduate of The New School, he is passionate about the arts, social justice, and all things nerdy. He can usually be found scouring the horror section of a local bookstore.

Contact InkTip